Green Seas: Decarbonising marine transport

To say that most global trade is reliant on the ocean would be an understatement. 80% of all international trade goods are carried by sea and that is continuing to grow year on year. We’ve already seen what damage just one shipping lane being blocked can do for global trade when in 2021 the Suez Canal was blocked by the Ever Given, a container ship that had run aground. But in spite of all this, international shipping only makes up 10% of global CO2 emissions created by transportation – that’s less than the entire aviation sector.

Of course, international shipping isn’t the only form of marine transport. Ferries, yachts, leisure craft and cruise liners all have their own impact on carbon emissions – and many have already taken big leaps towards decarbonisation.

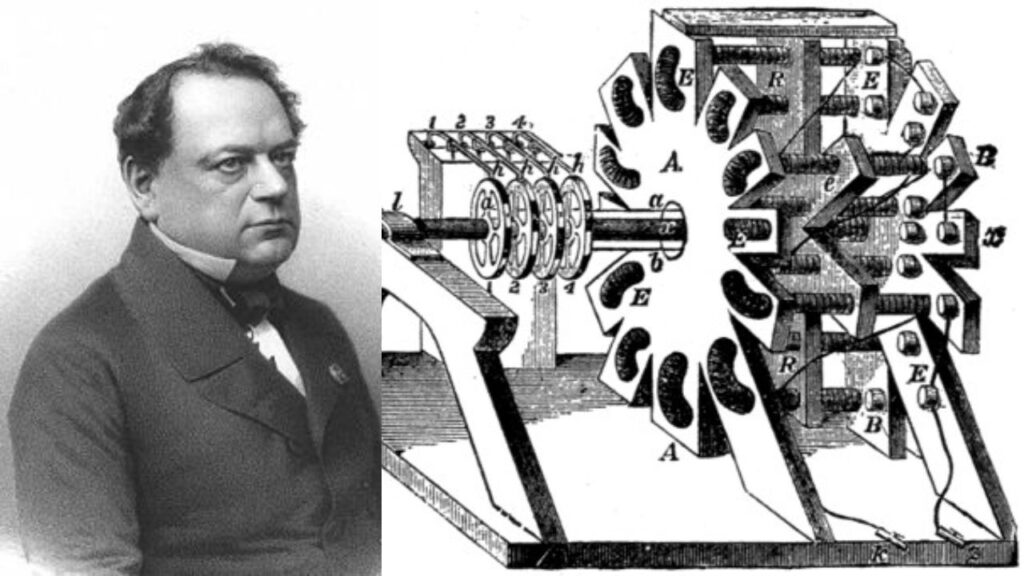

In fact, the earliest example of an electric boat dates back before we made started making ships out of materials other than wood. In 1838, Moritz Hermann von Jacobi, a Prussian-Russian engineer who studied and developed electric motors, created a 28-foot electric motorboat by fitting his motor into a ten-oared shallop with the backing of Tsar Nicholas I.

This technology was a foundational moment for the development of electric motors going forwards and it would be another ~50 years before anyone would think to use petrol to power a boat. Long before this, however, the use of steam to power ships was seen as the standard alternative to sailing and there was little desire or need for an electric motorboat.

Unlike most of the sectors we have explored in our articles on electrification and decarbonisation, boats are the only one to have been carbon neutral much longer than they have not. Sea transportation hasn’t relied on CO2 emitting technology for thousands of years, but, of course, where a carriage and horse isn’t a suitable replacement for a car’s engine, sails and oars aren’t ideal for most of the marine transport in use today. Even modern sailing ships like the world’s biggest Sail Yacht, KORU, uses two MTU diesel engines for power when the three sails aren’t or can’t be used.

So, what are the realistic alternatives to fossil fuel-powered engines that are available to manufacturers looking to decarbonise their marine transport offerings.

Battery Electric

We’ve already seen battery-electric technology capable of moving haul trucks as heavy as 200 tons across land, but that is nothing compared to the average-sized cargo ship which can weigh 165,000 tons. And where a mining vehicle will only have to move a few miles back and forth each day, cargo ships have to travel thousands of miles over the course of weeks or months.

But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible. The cargo ship, the Yara Birkeland, uses a 7 mWh battery to carry up to 100 cargo containers at a maximum speed of 15 knots (much slower than the 17-24 knots that bigger cargo ships can manage), but it is only a proof of concept and has shown that electric cargo ships, even if they’re on a smaller scale, can be manufactured.

However, where cargo ships might only have a recent proof of concept, other ship and boat types are pushing the (battery-electric powered) boat out even further in an effort to decarbonise.

In 2015, the MV Ampere (formally ZeroCat), a battery electric ferry capable of recharging in just 10 minutes, made its maiden voyage and is still in service today. And it is not the only battery-powered ferry that is in use. The Bastø Electric is the largest all-electric ferry, with a capacity of 600 passengers and as many as 200 cars. For large passenger transportation over shorter distances, battery electric might be the way – but for longer distances, we might have to look to the skies for inspiration.

Solar

As discussed in our article on the decarbonisation of the aviation sector; smaller planes have been using built-in solar panels to power their batteries over long distances. Well, where that wouldn’t have been as achievable on a larger scale because of weight, the opposite might be true for boats and ships.

Because ships have such a large surface area, it gives a lot more space to add solar panels without impacting the weight of the ship. Another Norwegian company, Hurtigruten, has revealed their concept for a zero-emission cruise ship which uses sails designed to have rotatable solar panels on, that can be turned to face the sun or folded down when not needed. These sails reduce energy consumption by 10% and the solar panels contribute another 2-3% in energy savings.

An early version of these sails is already being used on a hybrid industrial cargo ship, Canopée, which aims to reduce fuel consumption by almost a third.

By combining traditional designs with new thinking, the marine sector might have a new way to set sail towards decarbonisation. However, rebuilding or modifying ships is an incredibly costly endeavour that many shipping companies won’t do, so is there a fuel alternative that won’t require significant infrastructure changes?

Hydrogen

Hydrogen fuel regularly fluctuates in its position as an alternative fuel. It sees as many critics as EVs did 15 years ago, but once hydrogen fuel finds a confident footing in the market, it could be used to power ships and boats, passenger cars and commercial vehicles, or even trains.

But the biggest benefit to hydrogen that sets it above battery electric in many people’s minds is its ability to serve as an almost 1 to 1 replacement for diesel or petrol in an internal combustion engine. An ICE would need some modifications, a large air chamber for the combustion to take place in, but aside from that, hydrogen can be used in the same way as petrol.

For large ships, this is especially relevant as a criticism of hydrogen fuel is that it requires more space than a petrol or diesel tank, but Panamax cargo ships (the largest modern cargo ship type) carry between 2.5 and 3.5 million gallons of fuel. That’s more than five Olympic swimming pools’ worth of fuel. Sacrificing more space to eliminate carbon emissions will probably be worth it if more logistics and sea freight companies seek to reach net zero.

However, the more efficient usage of hydrogen (compared to combustion engines) would be in a fuel cell. We’ve seen fuel cell power applied on a smaller scale with vehicles like the Hynova 40, a 12m boat with a capacity of 12 passengers, but with the significant investment required to see fuel cell power available on the market on a massive scale, like with a cargo ship, it might be a few more years before we see these concepts made real.

It’s also worth mentioning how hydrogen fuel is created. As of 2021, 98% of all hydrogen was from natural gas (76%) or coal gasification (22%), with the last 2% coming from the electrolysis of water. Electrolysis has gained more ground over the last few years, now creating about 5% of hydrogen fuel, but there is still a long way to go. When powered by renewable energy like solar, wind or hydro-electric, electrolysis creates completely carbon neutral hydrogen fuel and since boats travel on water, they have an almost endless supply of salt water which is perfect for electrolysis.

That concept has already been fully realised by Energy Observer (pictured above), a completely self-sufficient boat producing no CO2 emissions. By utilising sails (Oceanwings®️), solar panels and hydrogen fuel made through electrolysis as it moves, the Energy Observer proves that by taking new innovations in fuel cell technology, boat design, solar panel and battery technology and so much more, you can create a truly carbon neutral transport sector with marine technology.

It will take investments into both the energy sector and into marine manufacturing but, it’s clear to see that carbon neutral transport at sea might be closer than that on our roads. Whether though battery technology, hydrogen, or a combination of both, there is a big opportunity for massive developments across the industry – but if it’s not driven by policy, will big companies make the investment?